The Forgotten First Ladies

by Naomi Yavneh Klos, Ph.D.

“The public mind seems not to be yet settled on the Vice President. The question has been supposed to lie between Hancock & Adams. The former is far the more popular man in N. England, but he has declared to his lady, it is said, that she had once been the first in America, & he wd. never make her the second.” -- James Madison, October 28, 1788This excerpt from James Madison’s letter to Edmund Randolph is surprising for two reasons. First, the use of the term “First Lady” to describe the president’s wife is generally thought to have begun some time in the 19th century. While Martha Washington was frequently referred to as “Lady Washington” in her lifetime, a Mrs. Sigourney is credited with using the phrase for the very first time in a profile of Martha published in the Boston Currier on June 12, 1843. Subsequently, President Zachary Taylor is said to have referred to Dolley Madison as “First Lady” in his 1849 eulogy at her state funeral, but there is no extant text of his remarks. The expression began to be somewhat popular a decade later, when Harriet Lane, niece of bachelor President Buchanan, was referred to in an 1860 article as “First Lady of the Land.”

Madison’s comment is remarkable, however, not just for its seemingly anachronistic terminology, but also because of its subject. Martha Washington is, after all, universally recognized as the United States’ first First Lady – whether or not that term was in use at the time. To whom is Madison referring?

Throughout American history, the First Lady has played an important role in hospitality. She serves and has served as hostess, adviser and, often, social activist – even before the Constitution of 1787.

In 1776, George Washington served as the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army but he was not the President of the United States; John Hancock was the elected President of the Continental Congress and in that position he signed the Declaration of Independence. As President, Mr. Hancock was considered the new nation’s Head of State. The Commander-in-Chief’s wife, Martha Washington, and the Continental Congress President’s wife, Dorothy Hancock, each took on the responsibilities of providing hospitality to important figures of the day.

In Philadelphia, “Dolly” Hancock helped her husband not only by hosting dinners for congressmen and foreign visitors, but with basic tasks like trimming the rough edges off the paper money printed by Congress, and packing it into saddle bags to be carried to different parts of the country. John Adams describes Dorothy in a letter sent home to his wife, Abigail, on November 4, 1775:

Two Pair of Colours belonging to the Seventh Regiment, were brought here last night from Chambly, and hung up in Mrs. Hancocks Chamber with great Splendor and Elegance. That Lady sends her Compliments and good Wishes. Among an hundred Men, almost at this House she lives and behaves with Modesty, Decency, Dignity and Discretion I assure you. Her Behaviour is easy and genteel. She avoids talking upon Politicks. In large and mixed Companies she is totally silent, as a Lady ought to be—but whether her Eyes are so penetrating and her Attention so quick, to the Words, Looks, Gestures, sentiments &c. of the Company, as yours would be, saucy as you are this Way, I wont say.

Martha Washington remained wife of the commander-in-chief until her husband resigned his commission on December 23, 1783, following the signing of the Treaty of Paris in September. (She of course resumed that role, as well as serving as the wife of the nation’s chief executive, upon Washington’s inauguration in 1789 as President and Commander in Chief.)

But the President of the Continental Congress served a year or less. And this tradition became codified under the Articles of Confederation, which not only further limited the president’s congressional powers, it specified a one-year term, with no possibility of re-election.

Martha Huntington, wife of the Continental Congress and USCA President Samuel Huntington, did not originally travel to Philadelphia upon his assuming the presidency on September 29, 1779, but she joined him when his term was extended into a second year. In 1780, after Congress provided him with a proper house and servants, a post rider was sent with a carriage to Norwich, from which she was escorted, according to the newspaper, “by a number of gentlemen and ladies of the first character.” Like Dolly Hancock before her, First Lady Martha Huntington was a generous and quiet hostess who, according to the Marquis de Chastellux, “served everybody, but spoke to no one.”

|

| Annis Boudinot Stockton |

Bring now ye Muses from th' Aonian grove,

The wreath of victory which the sisters wove,

Wove and laid up in Mars' most awful fane,

To crown our Hero on Virginia's plain.

See! from Castalia's sacred fount they haste,

And now, already, on his brow 'tis plac'd;

The trump of fame proclaims aloud the joy,

AND WASHINGTON IS CROWN'D, re-echo's to the sky. (ll. 1-8)

Although The Articles of Confederation would be completely replaced by the Constitution upon its ratification at the beginning of 1789, the dinners hosted by President Cyrus Griffin and his wife, Lady Christina, were designed to bring together political opponents in a social setting, to work together on important Congressional issues of the day. Cyrus had met Christina, daughter of the Scottish Earl of Traquair, when he was studying law in Edinburgh; despite religious differences, the two married. Abigail and John Adams’ daughter, Abigail Adams Smith, provided her mother this brief overview of the social week circle during the last months of the United States in Congress Assembled:

The President [Cyrus Griffin] is said to be a worthy man; his lady is a Scotch woman, with the title of Lady Christina Griffin; she is out of health, but appears to be a friendly disposed woman; we are engaged to dine there next Tuesday…

The President of Congress gives a dinner one or two or more days every week, to twenty person, gentlemen and ladies. Mr. Jay, I believe, gives a dinner almost ever week: besides the corps diplomatique on Tuesday evenings, Miss Van Berkell and Lady Temple see company; on Thursdays, Mrs. Jay and Mrs. Laforey, the wife of the French Consul, on Fridays; Lady Christiana, the Presidentess; and on Saturdays, Mrs. Secretary ---. Papa knows her, and to be sure, she is a curiosity. (September 7, 1788).

*The Articles of Confederation limited the term of each USCA President to one year. Consequently, each President remained in office until the one year term expiration, unless the USCA President resigned or another Delegate was elected in his place.

Capitals of the United Colonies and States of America

Philadelphia

|

Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774

| |

Philadelphia

|

May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776

| |

Baltimore

|

Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777

| |

Philadelphia

|

March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777

| |

Lancaster

|

September 27, 1777

| |

York

|

Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778

| |

Philadelphia

|

July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783

| |

Princeton

|

June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783

| |

Annapolis

|

Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784

| |

Trenton

|

Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784

| |

New York City

|

Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788

| |

New York City

|

October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789

| |

New York City

|

March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790

| |

Philadelphia

|

December 6,1790 to May 14, 1800

| |

Washington DC

|

November 17,1800 to Present

|

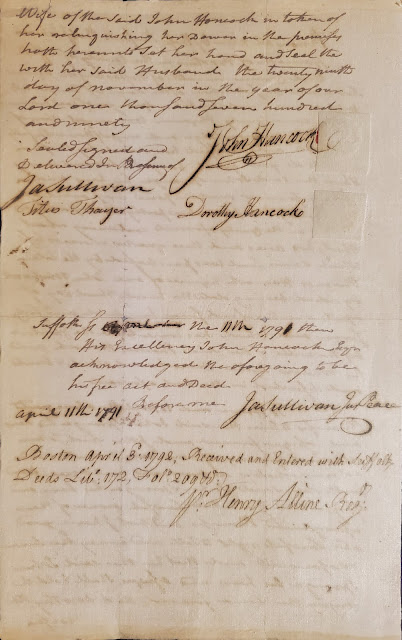

Manuscript Document Signed, “John Hancock”, with his wife’s signature underneath his, “Dorothy Hancock”. Two full pages, legal folio. Boston, November 29, 1790.

“Know all men by these presents that I John Hancock of Boston in the County of Suffolk and Commonwealth of Massachusetts Esquire for and in consideration of the sum of ten pounds paid me in hand by John Sprange of Deadham in the same County … the receipt whereof I do hereby acknowledge and myself therewith fully contented and satisfied have and by these presents do give grant bargain sell and convey to him the said John Sprange his heirs and assigns forever a certain piece or parcel of land lying in Braintree partly and partly in Milton in the county aforesaid containing about thirty-two acres and three quarters more or less which same land was purchased by the late Thomas Hancock Esquire of one John Washworth by a deed bearing date the twenty-third day of April one thousand seven hundred and forty seven and which has come to me the grantor by the wills of the said Thomas Hancock and his Widow Lydia Hancock and which is bounded and described in the deed aforesaid. To have and to hold the above granted premises to him the said John Sprange his heirs and assigns forever and of the said John Hancock for myself my heirs executors and administrators do covenant and agree to end with the said John Sprange his heirs and assigns that I am the lawful owner of the aforegranted premises and that I have good and lawful right to sell and convey the same as aforesaid and that he the said John Sprange his heirs and assigns shall hold and enjoy the same forever; and Dorothy the wife of the said John Hancock in taken of her … wishing her dower in the premises both hereunto let her hand and seal this with her said husband the twenty-ninth day of November in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and ninety, John Hancock, Dorothy Hancock. Sealed Signed and delivered in presence of Ja. Sullivan, Titus Thayer. Suffolk … the 11th 1791 then His Excellency John Hancock Esq. acknowledged the aforegoing to be his free act and deed before me, Ja. Sullivan Jus. Peace. April 11th, 1791. Boston, April 3d, 1792, Received and entered with Suffolk Deeds Lib: 172, Fol: 209 etc. Henry Alline Regstr.”

Dorothy Quincy married John Hancock in August of 1775, though prior to this she was reported to have had a crush on Aaron Burr. It was Hancock’s Aunt Lydia, that quashed those ideas, however, by abruptly ending a visit by Burr when he came to call upon her. She was witness to the Battle of Lexington, and was by default the first presidential secretary, while she assisted her husband with his work in the Continental Congress, as Hancock had no staff. This 1791 Deed has both the signature of our first Signer of the Declaration of Independence and his wife together on the same document. Dorothy Hancock's signature in her own right is nearly unobtainable. While not of the fabled stature of Abigail Adams, Martha Washington, or Dolley Madison, Mrs. Hancock was the First "First Lady" of the United States of America and should be honored as such.